-

Download -

Abstract: What are the different data components that Business Process Management Professionals hold at their disposal and how can the enterprise gain a maximum benefit from these? The present paper looks at the typical scenarios when it comes to harnessing the insights stemming from process data and to the new tendencies as well as technologies in that realm, specifically data mining and process mining.

By: Kay Winkler, Director and Partner NSI (Negocios y Soluciones Informáticas, S.A.) & Founder and president at ABPMP Central America and the Caribbean

Basic Information

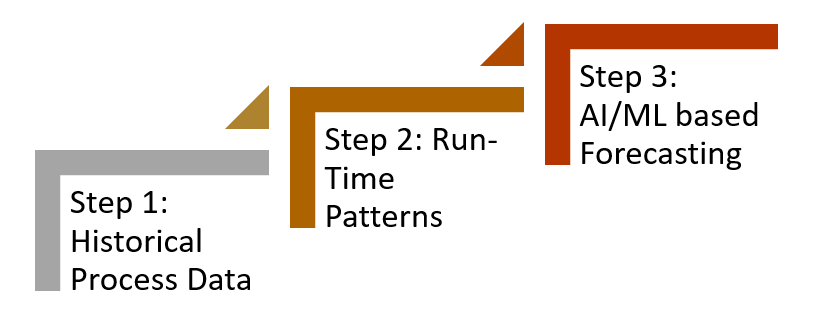

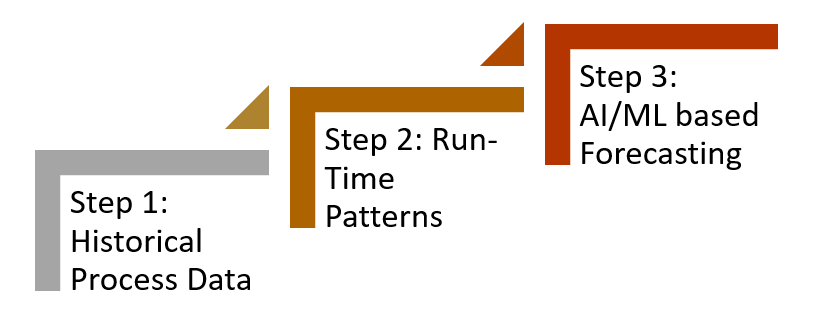

When dealing with BPM (and RPA to some extend), business and process analysts typically face at least 2 important data pillars: transactional BPM based data and form & integration-based business data. This paper will go into the innards and usage scenarios of both sets, paving the way towards advanced analytic strategies, using machine learning, decision tree diagrams, sentiment analytics and more. Process users on one hand must gain a firm purchase on the run-time behavioral patterns, the in-depth analysis of historical data sets, and, on the other hand, have to increasingly combine existing information effectively in order to produce quality forecasts that then in turn feed into the process rules logic, adaptively. That’s no small feat, especially considering that most users are still struggling with the most basic kinds of process data analytics: the review and interpretation of historical BPM data.

Figure 1 - Macro evolution of BPM Data; Winkler, Kay; 2019

Latest at the formal inclusion of dedicated toolsets for process analytics as a criterion to be considered an iBPMS vendor by the analysts, advanced forecasting that derive from business process data, has become a standard requirement by BPM users all over the globe.

Reports or – even more rudimentary – stored, raw process data could be described as the last piece of the “basic” elements of a BPM implementation. Now, while certainly advanced reporting, BAM, pattern recognition and predictive analytics are powerful features to accompany a process automation, covering the first elementary step of making sure that all the process as well as the business (form) data is stored in an automated, uniform, accumulative and (very important) scalable fashion – throughout all implemented business processes – is far more crucial (and more often than not something overlooked) for gaining real process insights and such enabling continued improvements. The key ingredients for viable business reports are in part derivatives of the process and form-variable design efforts and also in part the understanding of well-defined process metrics.

Of Process and Business Data

Having to deal with not only the statistical expressions of the process behavior but also its effects on the business end of things, certainly adds to the complexity a BPM analyst faces on a daily level but also – and more importantly – provides the users with the grand opportunity to gain an understanding of the causes and effects the process performance exercises on real life business outcomes. Add to the obvious advantages of continuously optimizing processes with these enhanced data sets the availability of increasingly more intuitive data science applications, it becomes clear why many experts in the industry confirm that BPM users are starting to take advantage of data science tool sets for process optimization to such a degree that analytics such as Data Mining have been adapted and coined as Process Mining in the field. And this for good reasons! On a per process bases, the process analyst can achieve quite the effect of scaled economies, given that with a relative few dependent and independent variables great insights on mission critical, end-to-end processes can be won (an example of such a variable will be detailed in a later paragraph).

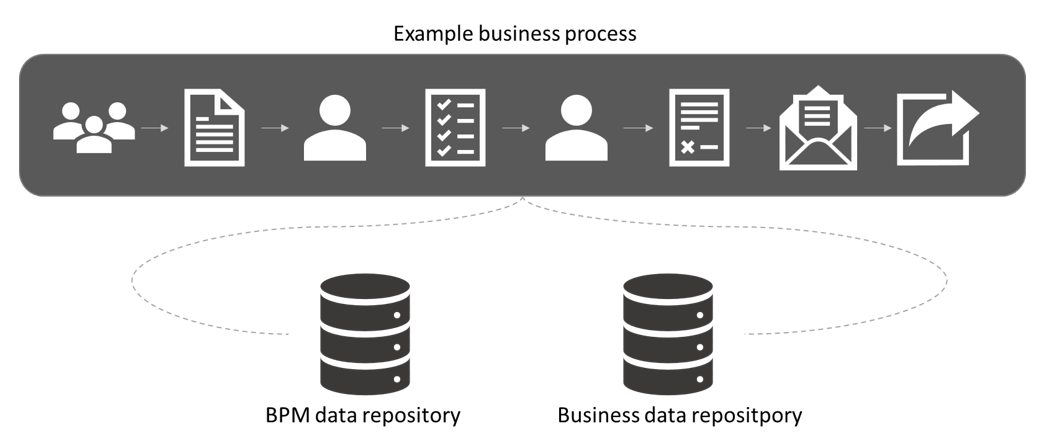

As hinted on above, a typical BPMS produces (at least) two distinct sets of data that can be either attributed to information indicative to the elements of the business process as a such or to the data said process handles; be it through its forms, integrations to other processes or through integrations that feed and read data from and to outside applications.

Figure 2 – Business and Process Data in BPM; Winkler, Kay; 2019

A typical example would be as follows:

- For the BPM data repository (not in any specific order)

- ID (Unique process incident or case ID)

- Initial date (Date when the incident/case has been “launched”)

- Initiator (User who initiated the incident/case; can be a named or anonymous user that can be later identified through other means)

- Concluded (Tag to identify if and how the incident has been concluded; for example: not concluded/still ongoing, concluded through case abortion etc.)

- Conclusion date (Date stamp if applies)

- Life cycle (Time stamp, if applies of incident/case duration)

- Current process step (In which process step is the incident/case currently located?)

- Assignment date (When has been the incident/case been assigned it its present process step?)

- Assigned Users (To whom has the incident/case been assigned to?)

- Assigned Role (To which role/group does the assigned user belong to?)

Besides the essentials above, there of course can be many other, additional variables a given BPMS captures. It’s important to notice that commonly this information is being “recorded” by most BPM platforms automatically and accumulatively, independent from whatever processes the engine handles. In that sense, one would have access to all the relevant BPM information regardless of the user’s decision to use the BPM platform for automating a procurement or a vacation request process, for example.

With this information on its own a lot of knowledge can be gained. For instance, time per process and case can measured (more details on that below) and process based KPI’s can be formulated (for example a goal of a vacation request that’s not supposed to exceed 1 working day until decisioning and not longer than 2 working days until an approved request gets logged into the HR systems and notified to all involved users).

- On the other one would have access to the wide variety of process dependent data which clearly depends on the specific business scenario the automation solution has been implemented for. This data can therefore be as diverse as the company’s different processes, its forms as well as internal functions (business rules, calculations, integrations and so forth). In the vacation request process example from before for example, typical process specific data artifacts would be:

- Requester name, ID etc. (data likely to be declared in the form)

- Requester department (data likely to be declared in the form)

- Request approvers (likely the result of a business rule in conjunction with an integration to the active directory)

- Requested dates (declared data)

- Remainder of available vacation days (business rule with a calculation and likely an integration to the HR repositories)

- Decisions and reason codes (in case of rejections).

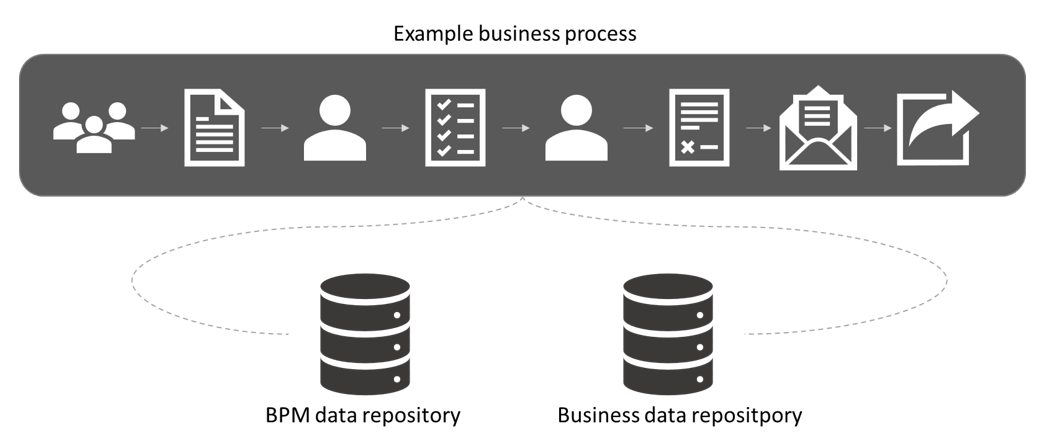

Both sets of information are of very indicative nature on their own but provide exponential insights when combined. Now, interesting correlations can be analyzed in the pursuit of continued operative improvements. Analysts will be able to detect, track and act upon patterns that stem from the influences that a specific user has on response times and case volumes, for example. In our example it would be of interest determining if vacation requests are being more likely to be reviewed late by a specific user and if these tendencies are altered by seasons, cycles or specific dates.

As a response, dynamic rules can then be implemented into the business process, provisioning alternative or additional resources if a given tendency breaches an established tolerance threshold.

Figure 3 – Business and Process Data analytics example in BPM, Winkler, Kay; 2019

Download the file to read the full version.

- For the BPM data repository (not in any specific order)